Pywells in Leicestershire

Underlined text in red is a link to a document

A note on the back of this photo says L-

I have a family photo of Ethel May on the back of which it says nee Jackson. However Ethel May was clearly a Coleman, but her (half) sister Kate was born a Jackson in 1903.

Another family photo (below) claims to shows her sister Winnie, who I never met, and her half sister Kate. However, I’ve discovered that there was another sister, Gladys, so the identities of the children in the photo may be in doubt.

This is the history of the Coleman/Jackson family:

William Henry Coleman (1871-

- Winifred Ivy (Coleman) born c1891 in Launceston

- Gladys Lilian W (Coleman) born c1893 in Devonport

- Ethel May Scown (Coleman) born 10 December 1895 in Stoke Damerel

Scown was Ethel’s grandmother’s maiden name.

William died in Devonport in 1899 at the age of only 28, and two years later Jessie

remarried, to a stoker in the Royal Navy -

Jessie then died in 1907, and Thomas John Jackson remarried, to Margaret Alexandra Dimmick (born in Londonderry) in Plymouth in 1908.

By the time of the 1911 Census, only Kate was living with her father and (by that

time) stepmother, along with Alfred Charles Dimmick who was a lodger and probably

Margaret’s brother. From those 1911 Census records Winnie, Gladys and Ethel can

be found in domestic service in Devon and Cornwall -

Grandma Ethel May Coleman’s Family

Above -

Kate and Tom had two sons, Peter and Terry (Anthony Terence). Terry was married in 1961 to Gwenda Wilkin who was a professional accordianist. During the 1960’s if I was at home during the day my mother would occasionally call out to me to say “Gwenda’s on the wireless”, and we’d stop to listen to her on Worker’s Playtime or Music While You Work on the BBC “Light Programme”.

Great Aunt Kate had a badly broken nose, which I was always told happened when her

stepmother hit her with a poker. The family history certainly seems to have been

complicated -

When we visited as a family in the 50s Kate lived in Weston Super Mare in Somerset with her husband Tom Mulvaney who she married in 1928 in Hendon. By the time I knew him Tom was blind because of his diabetes.

We sometimes stayed for a day or two and would sleep on “Z Beds” that folded up into small bedside tables.

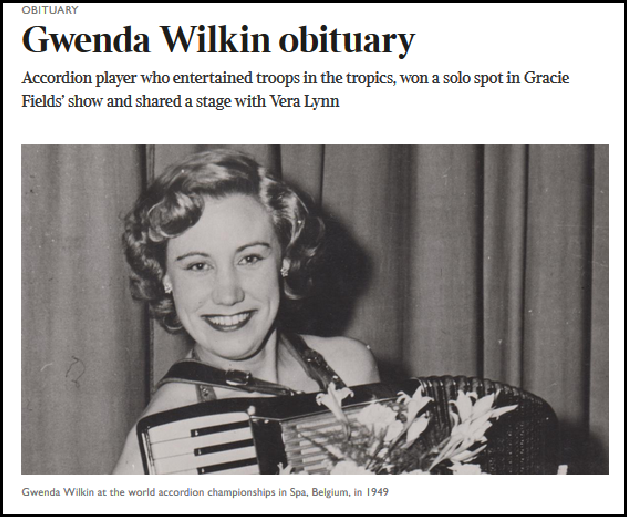

The following is transcribed from a (rather blurred) photograph of the Times Register of Tuesday May 19th 2020. There are some date inconsistencies noted in brackets

Gwenda Wilkin was giving an accordion recital for British troops in a jungle clearing when she noticed the last row of the audience had their backs to her. Coming off the makeshift stage she inquired why. “They are keeping an eye out for snipers” was the response. The war was over, but insurgents were still a threat.

For more than three decades Wilkin performed for military operations, at holiday

camps, in music halls, with orchestras and on radio, television and records. She

gave concerts in deserts, jungles and bombed-

One of her party pieces was an arrangement of Liszt’s Hungarian rhapsodies, for which she would be joined on stage by Danny, her mongrel who would howl in time to the music. Another was Hermann Koenig’s Post Horn gallop in which she would race her accompanying pianist to the end.

Having been taught to sew by her aunt Rosa King, a wardrobe mistress for London theatres,

Wilkin designed and made her own colourful stage clothes, insisting that the soldiers

needed to see someone bright, happy and smiling. On one occasion she came back from

a tour of Asia with reams of exquisite material that she transformed into sparkling

outfits. A circus clown taught her to do make-

Wilkin, who in 1978 took part in a concert at Buckingham Palace for the Not Forgotten Association starring Vera Lynn, was a frequent visitor to Clarence House as a guest of the Queen Mother or Princess Alice. She would dress in her ball gown and sequins before being collected by car. On one occasion they were running late and the driver was speeding on The Mall when they were pulled over by a police officer who leant through the window to chastise the occupants, only to pull back sharply and declare “Good evening your royal highness”.

She recalled her postwar travels to the tropics to entertain the troops with Lynn

and how on one occasion after the show they were escorted to their bedrooms and given

a box. The instructions were to close the mosquito net around them, and then open

the box to release a harmless gecko, a lizard-

Gwenda Violet Wilkin was born in London in 1933, the only child of Frederick Wilkin, a farrier, and his wife Lilian (nee Leith) (Turner?). She was soon showing exceptional musical promise, shining on violin, piano and accordion, which she studied with a series of Italian emigrees, notably Adrian Dante. “She knew the instrument inside out” said her daughter, who recalled her mother being able to build an accordion.

Her education at Sir George Monoux Grammar School, Walthamstow, ended when she was

expelled in 1947 for entering a music competition called Picture Page. Her entry

came to light because the headmistress saw her on television and declared it to be

“unbecoming of a young lady”. The following year she won the All-

By the age of 16 Wilkin was travelling extensively, including taking part at short notice in the world accordion championship at Spa, in Belgium, where the original British entry pulled out because of stage fright. She came a respectable sixth and the following year took third place when the contest was held in Milan.

In 1949, the same year that she appeared on Opportunity Knocks, a small article in

Musical Express announced that the 18-

Wilkin was giving a show for the Royal Navy in 1962 when the lighting blew and the

stage was plunged into darkness. “Get Terry”, cried the sailors. Terry, an engineer

whose real name was Anthony Mulvaney, appeared, fixed the lights and invited the

star on a date. They were married six weeks later (1961?), but Mulvaney was from

an Irish-

Mulvaney, who later worked at the Barbican Centre in London, died in 1985 (13 March

1992?), and Wilkin is survived by their children, Patrick, who is a printer in Ireland,

and Katy, a sales manager for a property developer in Cyprus. When they were small

Wilkin would take them on tour. “We were dressing-

One summer Wilkin was playing a season in Cornwall and took the opportunity to learn to drive. Her instructor made no secret of his disapproval of women drivers and when, after only ten lessons, an opening arose for a test, he insisted on entering her, despite her protests that she was not ready. Regardless, she passed, and afterwards bought a car, driving herself around northeast London until almost the day she died.

By her early fifties Wilkin was feeling the strain of lugging a heavy accordion around

and keeping it strapped to her chest for more than an hour at a time. She retired

from the stage on medical advice and went on to study animal husbandry, working in

veterinary businesses in east London for many years. To the delight of her children

she would often bring home patients in need of 24-

At the age of 60 she acquired a private pilot’s licence and five years later started helicopter lessons. She travelled the world, using her daughter’s house in Cyprus as a launch pad for visits around the Middle East where, in her musical days, she had a natural habit of finding danger. She had been performing in Egypt in 1956 when the Suez crisis blew up, while on another occasion trouble flared while she was on a concert tour of Cyprus. “She had an armed escort around the island,” Katy said, “and on one occasion the officer suddenly shouted ‘Down’ and as they ducked the car was shot up.”

Gwenda Wilkin, accordion player, was born on May 20th 1933. She died following complications during surgery on May 6th 2020 aged 86

By coincidence the CIA (Confédération internationale des accordéonistes) organizes World Accordion Day on May 6th each year.